Reflective Images

This project was funded by the Arkansas Community Foundation, supported through grants from the Alice L. Walton Foundation, Olivia and Tom Walton through the Walton Family Foundation, as well additional funds from the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation.

All vignettes

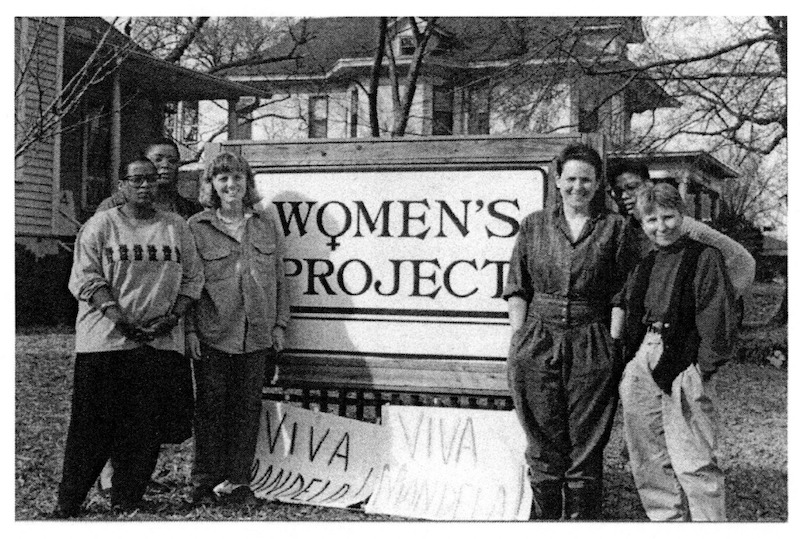

The Women’s Project represents a significant example of multiracial grassroots organizing in Arkansas History.

The Women’s Project began in Eureka Springs under the leadership of Suzanne Pharr. Originally called The Arkansas Women’s Training Project and incorporated as The Women’s Project in 1985, the organization supported and empowered Arkansas women through a multi-faceted and intersectional approach. Pharr stated in 1981 “Given a world of equality you would not need special groups, but women have special needs that have to be taken care of.” Arkansas women had plenty of needs in the 1980s mainly because of the layered oppressions of: poverty, sexism, domestic violence, and employment discrimination. Women were paid significantly less than men and more likely to be single parents and live below the federal poverty line. “Very few women in Arkansas make over $10,000 a year. A lot still needs to be done for women here.” Pharr told the Arkansas Gazette. For Black women and Queer women, racism and homophobia exacerbated these issues. Black women were even less likely than white women to be hired for jobs and when they were hired, they were paid less than white female counterparts. The Women’s Project facilitated increased union representation in the state, fought for increasing the minimum wage, and increasing access to childcare and healthcare.

Violence was one of the biggest issues facing women and connecting the Women’s Project to local communities proved an important element of organizing. Domestic violence often remained unreported to local authorities as women sought help from other local women. Knowing this, the Project worked with local women and organizations to get funding for battered women’s shelters. Leaders like Betty Overton and Janet Perkins helped facilitate important consciousness raising discussions among women in small Delta towns. For some, these discussions provided the first opportunity to seek help from other women enduring similar experiences. The Project hosted talks around the state like “Rape as Biased Violence” and spoke about how violence against women hurts everyone. Pharr told the Arkansas Democrat in 1991 “until violence against women and children is taken seriously, this world will not be safe for anyone.”

The organization also spoke out against homophobia and combated the HIV/AIDS crisis. Kerry Lobel led these efforts. When Governor Bill Clinton allegedly laughed at an offensive joke about lesbians in 1991, Lobel did not see the humor. “I think that is incredibly distressing and disgusting,” she said. Violence against LGBTQ+ individuals had been reported around the state. Lobel organized information sessions and edited a book about lesbian battering in an effort to increase public awareness of violence against lesbians.

While the HIV/AIDS crisis was largely viewed as affecting gay men, Lobel and other Women’s Project leaders sought to help female sex workers, addicts, and prisoners by educating them on the dangers of the virus. Women’s Project members distributed condoms and other tools to provide layers of protection. The organization obtained grants from the American Foundation for AIDS Research to support education programs in state prisons.

By the early 1990s, white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizing was on the increase around the state. The Women’s Project launched new initiatives aimed at keeping watch on these groups. The Watchcare Network was developed to be the “eyes and ears for justice” as these groups escalated their rhetoric, public displays, and tactics. Volunteers from around the state sent newspaper clippings and updates to the main Women’s Project Office in Little Rock. Project leader Kelly Mitchell-Clark explained the importance of this Network: “we were trying to establish this effort to track hate crimes, hate violence, and to figure out what would the community responses be and how could Arkansas craft a multiracial, multi-generation response that says this is not the kind of state we want.”

The Women’s Project is an example of what grassroots collective organizing can be when the efforts are multiracial and intersectional. The Project not only acknowledged issues facing women, but went further to identify how the oppressions of racism and homophobia created additional problems for specific women. The issues The Women’s Project combated were complex and so their responses were deliberate, calculated, and multilayered. There were no simple solutions. That made their efforts more difficult but also all the more important.

Sources

Main resource for this article is the amazing Women’s Project website that has articles, images, videos, and oral histories.

Additional:

“The Women’s Project” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Accessed here.

“Project Helps Women’s Groups” Arkansas Gazette, January 29, 1981.

“Grant Enables Feminist to Organize State’s Women” Arkansas Democrat, March 1, 1981.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 9, 1991.

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 20, 1991.